Internal processing

Internally, Zeebe is implemented as a collection of stream processors working on record streams (partitions). The stream processing model is used since it is a unified approach to provide:

- Command protocol (request-response),

- Record export (streaming),

- Process evaluation (asynchronous background tasks)

Record export solves the history problem and the stream provides the kind of exhaustive audit log a workflow engine needs to produce.

State machines

Zeebe manages stateful entities: jobs, processes, etc. Internally, these entities are implemented as state machines managed by a stream processor.

An instance of a state machine is always in one of several logical states. From each state, a set of transitions defines the next possible states. Transitioning into a new state may produce outputs/side effects.

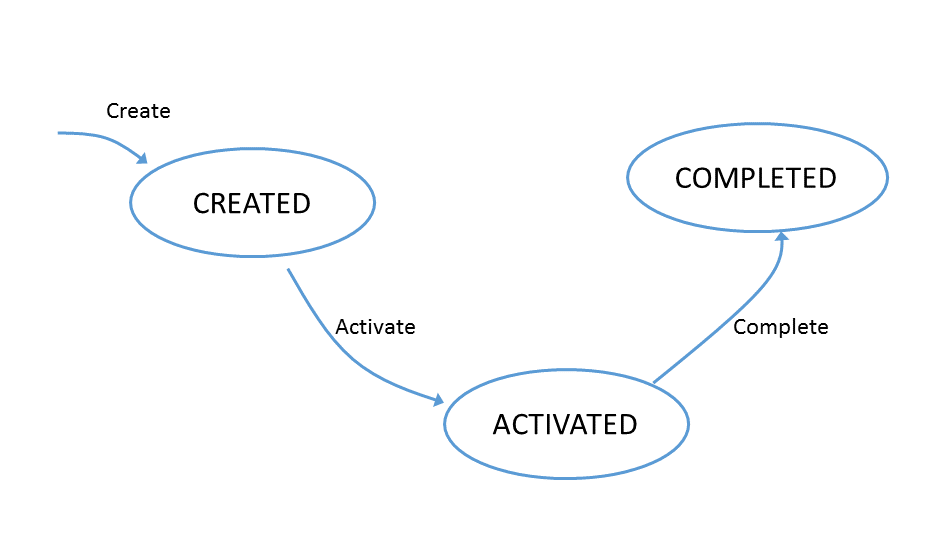

Let's look at the state machine for jobs:

Every oval is a state. Every arrow is a state transition. Note how each state transition is only applicable in a specific state. For example, it is not possible to complete a job when it is in state CREATED.

Events and commands

Every state change in a state machine is called an event. Zeebe publishes every event as a record on the stream.

State changes can be requested by submitting a command. A Zeebe broker receives commands from two sources:

- Clients send commands remotely. For example, Deploying processes, starting process instances, creating and completing jobs, etc.

- The broker itself generates commands. For example, locking a job for exclusive processing by a worker.

Once received, a command is published as a record on the addressed stream.

Stateful stream processing

A stream processor reads the record stream sequentially and interprets the commands with respect to the addressed entity's lifecycle. More specifically, a stream processor repeatedly performs the following steps:

- Consume the next command from the stream.

- Determine whether the command is applicable based on the state lifecycle and the entity's current state.

- If the command is applicable, apply it to the state machine. If the command was sent by a client, send a reply/response.

- If the command is not applicable, reject it. If it was sent by a client, send an error reply/response.

- Publish an event reporting the entity's new state.

For example, processing the Create Job command produces the event Job Created.

Driving the engine

As a workflow engine, Zeebe must continuously drive the execution of its processes. Zeebe achieves this by also writing follow-up commands to the stream as part of the processing of other commands.

For example, when the Complete Job command is processed, it does not just complete the job; it also writes the Complete Activity command for the corresponding service task. This command can in turn be processed, completing the service task and driving the execution of the process instance to the next step.

Handling back-pressure

When a broker receives a client request, it is written to the event stream first, and processed later by the stream processor. If the processing is slow or if there are many client requests in the stream, it might take too long for the processor to start processing the command. If the broker keeps accepting new requests from the client, the back log increases and the processing latency can grow beyond an acceptable time.

To avoid such problems, Zeebe employs a back-pressure mechanism. When the broker receives more requests than it can process with an acceptable latency, it rejects some requests.

The maximum rate of requests that can be processed by a broker depends on the processing capacity of the machine, the network latency, current load of the system, etc.

Hence, there is no fixed limit configured in Zeebe for the maximum rate of requests it accepts. Instead, Zeebe uses an adaptive algorithm to dynamically determine the limit of the number of inflight requests (the requests that are accepted by the broker, but not yet processed).

The inflight request count is incremented when a request is accepted, and decremented when a response is sent back to the client. The broker rejects requests when the inflight request count reaches the limit.

When the broker rejects requests due to back-pressure, the clients can retry them with an appropriate retry strategy. If the rejection rate is high, it indicates that the broker is constantly under high load. In that case, it is recommended to reduce the request rate.